The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1–23.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2024.2310739 # 23 p.

The Andhra Pradesh Zero Budget Natural Farming project was implemented by India’s State of Andhra Pradesh in 2016 and renamed AP Community Managed Natural Farming (APCNF) in 2020.

APCNF is recognised as a successful example of peasant-led agroecology by social movements, multilateral UN bodies, governments, and researchers. This paper offers more critical perspectives here, and argue that this agroecology model deepens inequality and dispossession.

The Andhra Pradesh Climate Resilient Community Managed Natural Farming (APCNF) is a state-promoted agroecology model aiming to transition six million farmers and eight million hectares of land to entirely chemical-free farming. APCNF is anchored by Rythu Sadhikara Samastha (RySS), a government-owned private limited company conceptualised by the Andhra Pradesh government and the World Bank.

APCNF is recognised as a successful example of peasant-led agroecology by social movements, multilateral UN bodies, governments, and researchers. This paper offers more critical perspectives here, and argue that this agroecology model deepens inequality and dispossession.

Despite claims to the contrary, APCNF is locked in an unchanged productivist paradigm controlled by capital in collaboration with the state. By co-opting agroecology, APCNF closes down options for a just transformation of the dominant agri-food regime.

Extracts of the article:

The Andhra Pradesh (AP) and Telangana states clearly demonstrated their desire to fast-track capitalisteconomic transformation, so much so that by 2016, a mere 18 months later, the World Bank ranked both AP and Telangana 1st in the country for ‘ease of doing business’ (GoI 2016; The World Bank, 2016). This was made possible by aggressive pro-capital, land, labour, tax, power, infrastructure, water and environment reforms, all of which severely undermined workers rights, landrights, and fast-tracked environmental destruction. (page 4)

In 2018, the Sustainable India Finance Facility, a partnership between the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF), and the bank BNP Paribas, signed an agreement with GoAP to facilitate a USD 2.3 billion investment to scale up ZBNF (BNP Paribas 2018; UNEP 2018). Sustainability Partnerships have also been signed with IDH, which is a consortium of top Global Corporate food and agriculture agribusiness players, digital data corporations, the World Bank, and researchers of market-based solutions to climate change, biodiversity and sustainable production. This corporate partnership aims to experiment with sustainable landscape sourcing (page 10)

Another recent public-private investment is via a Global Environment Facility (GEF) loan for ZBNF, with a contribution of USD 44 million private blended finance from the Bank BNP Paribas in the form of guarantees and equity funds (GEF 2021). This project aims to demonstrate how, ‘The avoided subsidies for synthetic fertilizers, could potentially free-up resources that can then be redirected to servicing loans from impact investors. (page 10)

Lack of access to land coupled with embedded discrimination and exclusionary practices are

core reasons for the minimal cattle livestock ownership amongst Dalit households. It can therefore be reasonably presumed that it is the dominant caste of land-owning farmers who are able to invest in desi cows, and start up APCNF biopesticide enterprises. This would result in further accumulation of wealth and assets in the hands of the haves. (page 12)

The APCNF agroecology programme rests on a superstructure of extreme inequality in land ownership (Rawal and Bansal 2021) and expanding landlessness amongst India’s most marginalised and discriminated-against citizens: Dalits, Adivasis, and Muslims. (page 5)

Between 2002 and 2012 tenancy showed a huge shift from shared tenancy to fixed rent tenancy in cash (29.9% to 55.6%), again significantly higher than all-India averages. This trend shifts the entire risk burden onto tenants and increases their vulnerability. Tenancy is also extremely high amongst socially marginalised communities. (page 6)

A recent APCNF study reports that 66% of APCNF farmers belong to historically privileged dominant castes termed Other Castes (OC) and OBC (Other Backward Classes) communities, with the remaining being Dalit (13%) and Adivasi (21%). Overall, there is very poor presence of women farmers in APCNF – a mere 5.9% of total APCNF farmers surveyed. (page 6)

APCNF studies also flag poor adoption of APCNF by tenant farmers, as the APCNF hinders their ability to pay land rents in the short term, even if there are financial gains in the long term. This reluctance of tenant farmers to adopt CNF continues to date. These findings are indicative of how critical it is for the state to execute redistributive land reforms to correct the massive inequality in land ownership. Equitable land reform is a pre-requisite for any kind of agroecological benefits accruing to the landless. (page 6)

Moreover, ZBNF/APCNF produce is being marketed via Producers Market (ProducersMarkets n.d.) which is a project of the Producers Trust, of which RySS is a Trade Collaborator (Producers Trust n.d.). This is a blockchain agri-tech start-up which has joined hands with IBM Food Trust to experiment with food traceability, and a technology-driven marketplace that links producers and consumers via big data technologies such as distributed ledger technologies, smart contracts, and cryptocurrency in the global multitrillion-dollar agriculture value chain. (page 10)

core reasons for the minimal cattle livestock ownership amongst Dalit households. It can therefore be reasonably presumed that it is the dominant caste of land-owning farmers who are able to invest in desi cows, and start up APCNF biopesticide enterprises. This would result in further accumulation of wealth and assets in the hands of the haves. (page 12)

APCNF is based on a heavily funded top-down, one-way pedagogy of knowledge creation and transmission by ‘experts’ – moulded on the brahminical construct of ‘Guru-Shishya Parampara’, or the guru-teacher. (page 13)

APCNF farmers thus produce for the market and are cogs in distant supply chains. The inequality of the system excludes the caste-oppressed agricultural workers from purchasing and consuming the higher priced ZBNF food that was produced by their alienated labour. The income they earn from this agroecological project will go to purchasing the cheapest ‘chemical food’ in the market. This raises fundamental questions about the APCNF agroecology project and the many studies which claim that APCNF increases ‘well being’, access to safe food, and wealth for farmers. In reality, APCNF is accumulating these benefits for the historically privileged landowning castes, whilst sustaining the larger meta-frame of inequality and discrimination. (page 14)

Related:

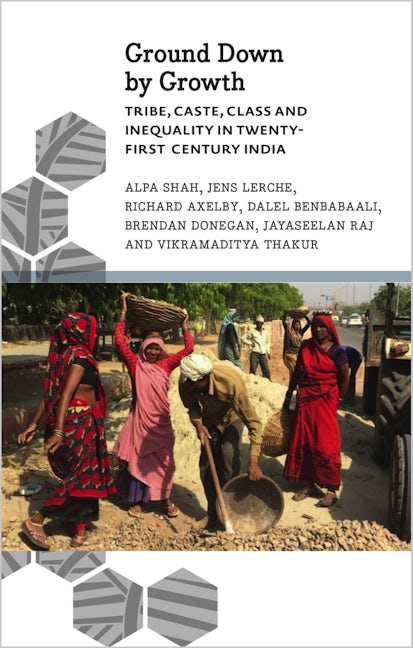

Alpa Shah, Jens Lerche, Richard Axelby, Dalel Benbabaali, Brendan Donegan, Jayaseelan Raj, and Vikramaditya Thakur. (2017) Ground Down by Growth: Tribe, Caste, Class and Inequality in Twenty-First-Century India. London: Pluto Press, 304 pp.

While the world marvels at India’s economic growth rates, inequality is rising and the country’s ‘untouchable’ and ‘tribal’ communities – who make up a staggering one in twenty-five people across the globe – remain at the bottom of the economic and social hierarchy. How and why is this the case? In conversation with economists, a team of anthropologists lived with Adivasis (‘tribes’) and Dalits (‘untouchables’) in five different sites across India to answer this question.

They show how capitalism is entrenching social difference, transforming traditional forms of identity-based discrimination into new mechanisms of exploitation and oppression. Inherited inequalities of power are merging with the super-exploitation of migrant labour, and the conjugated oppression of class, caste, tribe and gender. The struggles against these inequalities are considered.

About the author: Alpa Shah was raised in Nairobi, read Geography at Cambridge and completed her PhD in Anthropology at the London School of Economics, where she now teaches as Associate Professor.

Praveen Jha, Paris Yeros, Walter Chambati, and Freedom Mazwi (2022) Farming and Working Under Contract. Peasants and Workers in Global Agricultural Value Systems. #448 pp

This book examines the different types and models of contract farming in the global South. It reflects on the suitability of such private marketing arrangements for various crops, markets and farmers, on the basis of an analysis of the hegemonic relations between firms and farmers, better returns on crops and the extent of contract farming prevalent.

This book examines historical trends in agriculture and rural development at the sub-national level in India, taking Andhra Pradesh as a case study. It investigates agrarian development before and after the green revolution, and explores the impact of major paradigm shifts in agricultural development policy, including globalization and liberalization. The book also explores the changes in land use pattern, input usage and the performance of allied sectors, and institutions over the past fifty years under different policy scenarios.

This volume provides a comprehensive analysis of the macro- and micro-level issues associated with agrarian distress. It analyses structural, institutional, and policy changes, highlighting the failure of public support system in agriculture. The crisis manifests itself in the form of deceleration in growth and distress of farmers. The case studies from Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, and Punjab bring out the diversity of conditions prevalent in the states.

No comments:

Post a Comment