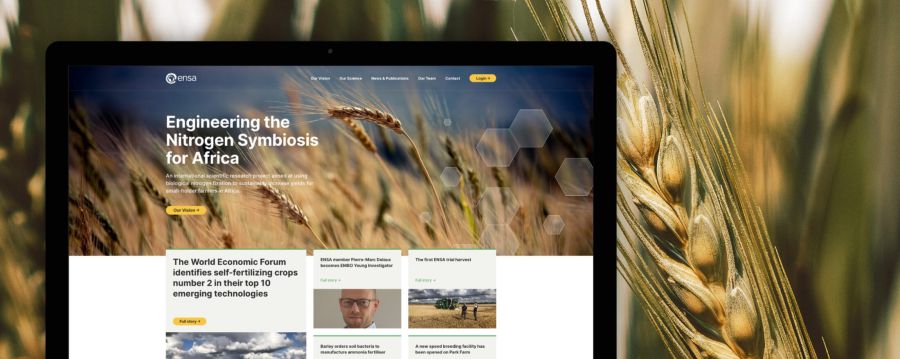

The Engineering the Nitrogen Symbiosis for Africa (ENSA) research programme utilises natural symbioses between plants, soil fungi and bacteria, that deliver nutrients to the plant. By leveraging these relationships ENSA aims to engineer crops to make better use of nutrients already present in the air and the soil. This would allow sustainable increases in crop yields, potentially revolutionising smallholder farming in low-and-middle-income-countries, while providing a viable solution to sustainable and secure food production in high-income countries.

The Cambridge-led consortium received $35m to boost crop production sustainably in sub-Saharan Africa. The grant, from Bill & Melinda Gates Agricultural Innovations (Gates Ag One), will enable researchers led by the University of Cambridge Crop Science Centre to engineer plants to take advantage of naturally occurring interactions with micro-organisms – fungi and bacteria – that help in the uptake of nutrients from the soil and air.

The grant funds the Engineering the Nitrogen Symbiosis for Africa (ENSA) research programme. ENSA is a Cambridge-led international collaboration with partners:

- University of Oxford, UK; NIAB, UK;

- Royal Holloway University of London, UK;

- Aarhus University, Denmark;

- Wageningen University and Research, The Netherlands;

- University of Freiburg, Germany;

- University of Toulouse III Paul Sabatier, France;

- University of Illinois, USA;

- Pennsylvania State University, USA.

“African agriculture is at an inflection point, with vastly increasing demand at a time when supply is at risk, especially due to a changing climate. The outcomes of this work have the potential to see gains as great as those from the Green Revolution, but without relying on costly and polluting inorganic fertilisers. Increasing sustainable production of crops in small-holder farming systems, like those in sub-Saharan Africa, directly addresses some of the worst poverty on the planet.” Giles Oldroyd, Director of the Crop Science Centre and Russell R Geiger Professor of Crop Science.

Legumes need less nitrogen fertiliser than cereal and other vegetable crops. A high-performing legume can fix up to 300kg of nitrogen per hectare, which would otherwise cost farmers around $1 per kg in fertiliser to meet the nutrient needs of the plant.

The Enabling Nutrient Symbioses in Agriculture project, is are trying to understand how exactly legumes do this. We are exploring how these nitrogen-fixing root nodules evolved in only legumes in the first place. With that knowledge, we hope to find ways to increase the efficiency of nitrogen fixation inside the root nodules and maximise the growth and yield of legume crops.

The Enabling Nutrient Symbioses in Agriculture project, is are trying to understand how exactly legumes do this. We are exploring how these nitrogen-fixing root nodules evolved in only legumes in the first place. With that knowledge, we hope to find ways to increase the efficiency of nitrogen fixation inside the root nodules and maximise the growth and yield of legume crops.

From lentils to chickpeas, and even the humble baked bean, pulses are perhaps best known as an alternative, plant-based source of protein. These plants are environmental heroes: they work together with soil microbes to “fix” nitrogen from the air, enriching the soil with nutrients to allow them to thrive.

As their nitrogen-fixing capacity is becoming better understood, scientists are hoping to find ways to increase productivity, and eventually apply some of these effective soil-enriching characteristics to other crops such as cereals. With the ability to fix nitrogen, crops would need less nitrogen fertiliser and soil health would simultaneously improve.

Pulses, the edible dry seeds of legume plants, are staple foods in the diets of both people and livestock around the world. Across Europe and the US, they are commonly eaten as tinned beans, chickpeas and lentils, while in sub-Saharan Africa, cowpea is among the most important legumes.

High in protein, carbohydrates, dietary fibres, vitamins and minerals, pulses play a fundamental role in nutritious healthy diets. Both the seeds and leaves are also used as feed for livestock. For smallholder farmers in developing nations, nutritious pulses are a cost-effective substitute for animal protein and make up a large proportion of typical diets.

As their nitrogen-fixing capacity is becoming better understood, scientists are hoping to find ways to increase productivity, and eventually apply some of these effective soil-enriching characteristics to other crops such as cereals. With the ability to fix nitrogen, crops would need less nitrogen fertiliser and soil health would simultaneously improve.

Pulses, the edible dry seeds of legume plants, are staple foods in the diets of both people and livestock around the world. Across Europe and the US, they are commonly eaten as tinned beans, chickpeas and lentils, while in sub-Saharan Africa, cowpea is among the most important legumes.

High in protein, carbohydrates, dietary fibres, vitamins and minerals, pulses play a fundamental role in nutritious healthy diets. Both the seeds and leaves are also used as feed for livestock. For smallholder farmers in developing nations, nutritious pulses are a cost-effective substitute for animal protein and make up a large proportion of typical diets.

No comments:

Post a Comment